Incantation of Reason Edition

“Lord, I believe; help my unbelief!” Remembering Frank Auerbach, remembering the Florence of 1504, evaluating the UFO religion, and more.

Friends,

High time as Winter descends to return to our roots, good old fashioned Miłosz-posting.

While praising the Polish poet, Santi Ruiz recently singled out Miłosz’s poem “Incantation,” which Ruiz used to think was “terribly corny.” Not anymore.

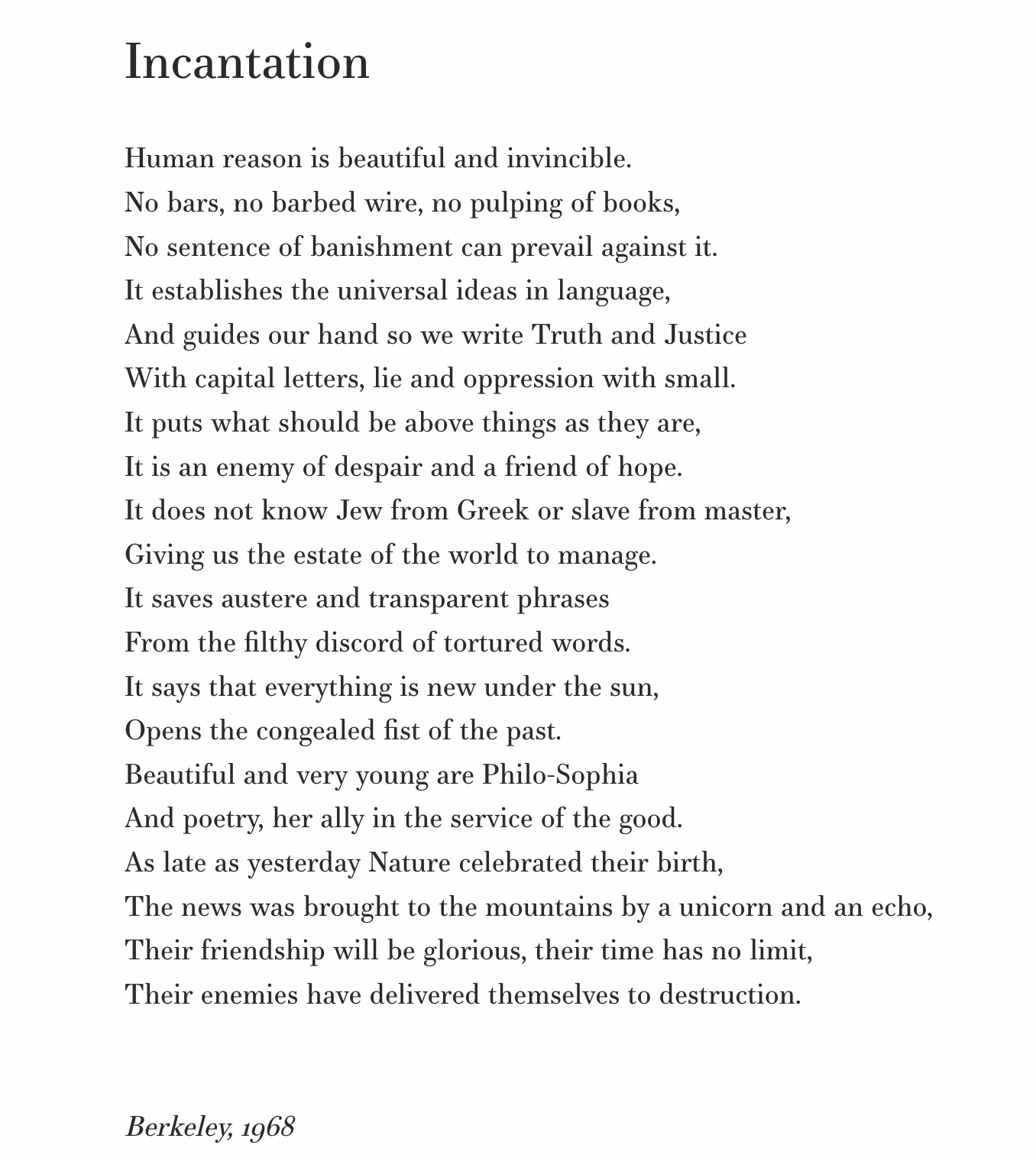

It’s true the tone of “Incantation” is notably idealistic compared with much of Milosz’s work. The key to reading it is, I think, to recognize the undercurrents of irony, paradoxical hesitancy, and compensatory enthusiasm. There’s a sense of the narrator “protesting too much,” grasping for solid ground.

That doesn’t necessarily mean Miłosz doesn’t believe his own words. He isn’t exactly being sarcastic in that aggressively bouyant opening line, so unlike his usual pessimism: “Human reason is beautiful and invincible.” But if he does believe it, it’s because he has to believe it, after living through several apocalypses laid end-to-end. Because he’s seen the consequence of abandoning faith in reason in favor of fashionable post-truth ideologies.

If he does believe it, he is also pushing himself to keep on believing it, because he often can’t bring himself to, and he sees the alternatives as horror, oppression, and despair. This double movement should feel familiar to all believers; it is the cry of the anguished father in Mark: “Lord, I believe; help my unbelief!” It’s important to remember that this sort of doubt is not the opposite of faith but intrinsic to it. Doubts and uncertainties are what make the action of faith, the affirmation of trust in something beyond us and higher than us, possible in the first place.

The language echoes Scripture throughout. It embraces the triumphalism of the Psalmist (enemies delivered to destruction), and the revolutionary equality of Paul (There is neither Jew nor Greek) while playfully inverting the pessimism of Qoheleth, who famously sighs that there is nothing new under the sun.

Like many of the Psalms it is intentionally hyperbolic, and like them its boasting confidence is actually a prayer, a petition, a way of pleading one’s case. Thus, an “incantation,” rather than an “argument” or even an “exhortation.” He is repeating these convictions ritually, liturgically, trying to inhabit them and lose himself in them and draw strength from them. Underneath the celebration of light and reason, one detects the lingering fear that it might not be so.

He pokes fun at this faith as well, a major reason why the poem escapes the purgatory of corniness. The reference to unicorns threatens to suddenly shift the poem’s moral force into the realm of the mythological, and in that hyperbole of “everything new under the sun,” we can detect a gentle teasing of zealous utopianism. Those familiar with the rest of Miłosz’s work, which celebrates the Particular over the abstract, should recognize that to him, putting “what should be above things as they are” is far from straightforwardly praiseworthy.

In a way he immediately answers his own doubts. He is saved from cynicism by his love of language. Language unites the Particular and the Universal. Language does not just label Things, nor only sort and organize them, but in some mysterious way it brings them into being. Elsewhere Miłosz writes: “What is pronounced strengthens itself / What is not pronounced tends to nonexistence.”

So he grounds poetry, not as a purely aesthetic pursuit nor as an escape from reality, but as something rooted in the earth, as an “ally” in the daily struggle to fight for the good and wisely manage the “estate of the world.” Miłosz is not a moralist by inclination, but over and over, almost against his better judgment, he commits himself to the battle against despair, nihilism, and relativism, with language as a gift-weapon from God in that battle, because it endows us with a special commission to participate in His life through participation in the Word that creates and structures the world.

To abuse language with “tortured words” is on a spiritual level an affront to that divine gift, and on the civilizational level an invitation for the arrival of “bars, barbed wire, and the pulping of books.”

He didn’t always seem to believe all this. In fact, it is tempting to put forward a reading of “Incantation” that is almost entirely ironic, in which the narrator is more or less parodic, more or less divorced from Miłosz’s own views, more or less completely deluded. One in which Miłosz is mocking the optimists, the way their hopes are crushed again and again, every day, within five minutes of getting out of bed.

But I don’t think so. There is too much sincere anguish underneath the bravado. I do think he would have known full well that his enthusiasm would be read as ambivalent, and was happy to ride that tension down the line of the poem and off into the sunset.

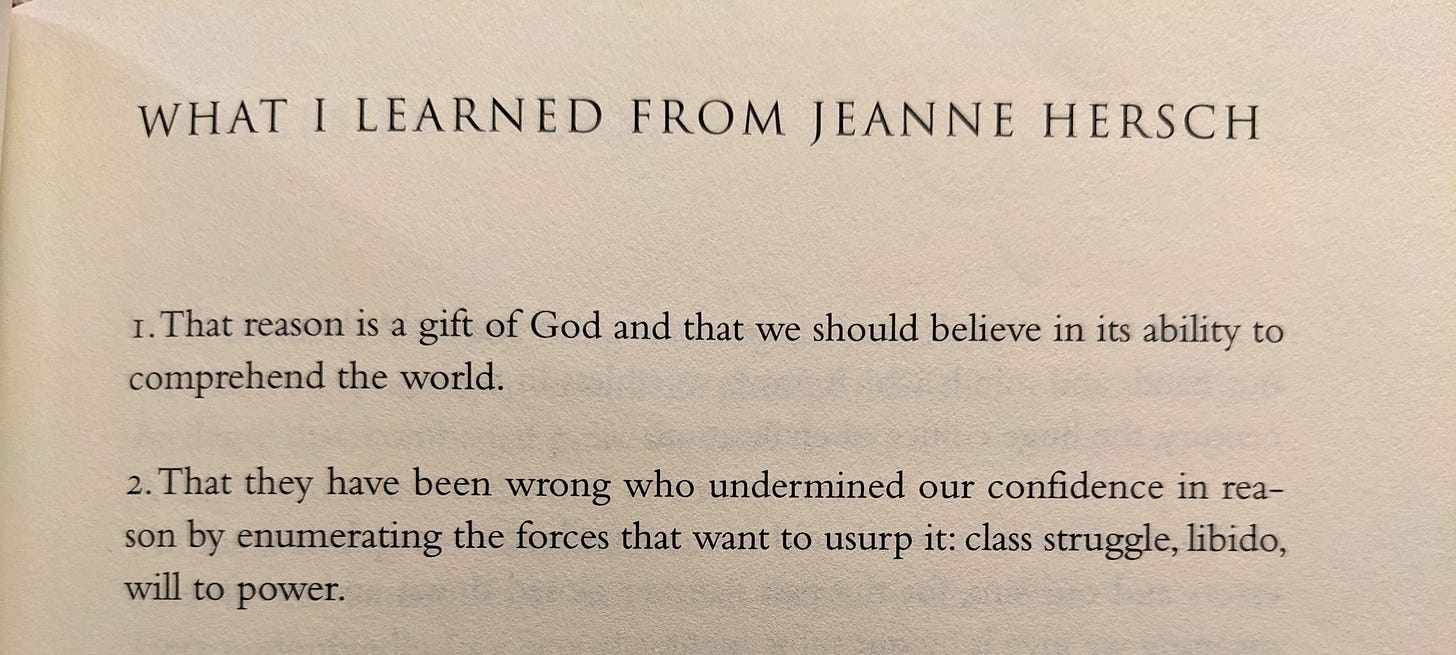

It was an ambivalence he never stopped grappling with. Toward the end of his life, he summarized the lessons of his decades-long argument with the Swiss-born philosopher Jeanne Hersch. First among them: “That reason is a gift of God and that we should believe in its ability to comprehend the world.”

It’s notable that this is among the things he “had to learn,” underscoring his natural skepticism. And implying that this education was still not fully complete in 2000, more than thirty years after the breathless claims of “Incantation.”

In his final collection, Second Space, he continues to grapple with both the intelligibility and the goodness of the world that God has made. His affirmations of both are not trumpeted from the mountaintops, as in “Incantation,” but now interiorly obsessed over, fondled in a worried palm, examined from all angles.

The long and winding “Treatise on Theology” opens with these lines, still held, despite their force, somewhat at a distance, gingerly, as if the poet fears that they may disintegrate into dust at any moment:

Why theology? Because the first must be first.

And first is a notion of truth…

Let reality return to our speech.

Amen.

Miłosz understands reason in a medieval sense, even a “Thomistic” sense… That is to say, he understands it in a way that precedes the great schism that placed the intellect of the rationalists on one side of the divide, while the other was occupied by the imagination and intelligence of the artists, who not infrequently take refuge in irrationality. Healing this divide—is it possible?—was and is one of Miłosz’s great utopian projects, the ambition of a writer who has himself done battle with so many other utopias.

—Adam Zagajewski

Links.

Remembering Frank Auerbach. “Auerbach will be remembered as a key part of the much-mythologised generation of the School of London, an outcast band of predominantly non-Londoners who found in the grit and grime of their adopted city enough material to invigorate a national ambition for Modernist painting. They winced away from the contemporary vogues for pure abstraction and minimalism and re-embraced the figure.”

Auerbach: “I started off as a superficial person who was attracted to the arts willy-nilly. The more I realised how difficult it was, the more I knew that it was a challenge, that I would feel I had wasted my life if I didn’t try to grapple with it.”

Who were the Wertheimers, the family that sat for a dozen Sargent paintings?

August Lamm on unorthodox holidays: “How does one seduce a bartender with a clear head and a stomach full of soup?”

Beowulf, Foucault, and other McCarthy influences.

(Most of you have probably already seen the other McCarthy gossip.)

Emma Hardy’s painful contribution to literature.

The misunderstood Impressionists.

Anna Krivolapova on internet-speak, Philip K. Dick, parapolitics, writing dialogue, Brautigan, Play It as It Lays, and much more.

Rose Lyddon on Jean Rhys: “Her most constant feeling was of rejection by the world. Not just individual people but the whole world—the great, hulking force of it.”

Florence in 1504, the annus mirabilus that saw Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Rafael working side-by-side: “The creation of David was a masterstroke: not only a sublime work of sculpture, but a stunning piece of civic propaganda: the underdog who slays the giant Goliath. A symbol of a city defiant in the face of her enemies.”

“Here lies Raphael, who in life Nature feared would best her, and in death feared she herself may die.”

—epitaph of Raphael, by Pietro Bembo

Ben Sixsmith on the afterlife of Father Jerzy Popiełuszko: “Catholic anti-communism represented a beacon of proud resistance to a corrupt establishment. Now, the Church is facing harder times while it is seen as being the establishment.”

Sam Buntz on the UFO religion: “It became clear to me that UFO mythos is the technologization of all myth.”

Zina Gomez-Liss reviews Anna Lewis’ debut poetry collection.

James Poulos on reviving the American tech tradition: “Innovation-forward culture may feel like a huge acceleration today, but it’s actually a return to the moral norm of Americans being and feeling comfortable, competent, and confident taking charge of their tools and toolmaking.”

Gregory Wolfe on the paradox of creativity, with a wonderful excerpt from Dorothy Sayers.

May all your myriad workshops both digital and analog be bright & merry & thrumming with the satisfaction of new creations,

As ever,

J

I always enjoy your posts. Thank you for mentioning my review. Have a blessed Advent!