Thankful Failure Edition

"To be like a beggar when it comes to writing music: whatever, however, and whenever God gives."

God says: Do what you will, and then pay for it.

—Spanish proverb

The artistic vocation is a difficult gift, a gift for which one must pay one’s entire life.

—Pope St. John Paul II

Buy the ticket, take the ride.

—Hunter Thompson

Friends,

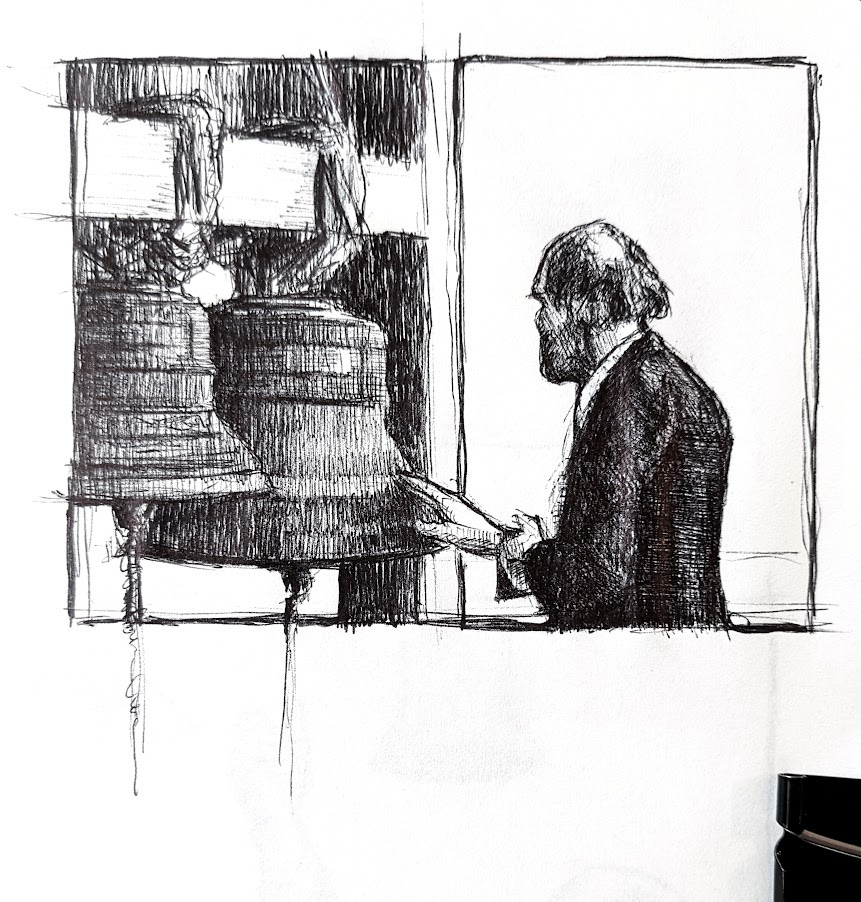

This month’s missive will be a bit different than usual. I have been on the road, first at my artist residency, and then visiting various family and friends on roadtrip arc crisscrossing the wilds of greater New England. My cup is overflowing: with sketches, half-begun paintings, hundreds of photo references, codices stuffed with clouds, new books, new vistas, and new companions on the creative journey. It will take some time to sift through and integrate all that I have gathered, enough fodder collected in a few short weeks to last me a year.

But I wanted to share with you something that gets at the heart of my experience at Mount Saviour Monastery. It is a brief address by the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, derived from his musical diaries. It was read to us by our retreat director and it immediately summed the vocation of the artist who seeks her source, her audience, and her duty first and foremost in God, in the Maker’s creative gift. It is about our greatest teacher, which is of course, failure. It is so beautiful. Please enjoy.

“Have you thanked God for this failure already?”

These unexpected words were said by a little girl. I remember exactly: it was July 25th, 1976. I was sitting in the monastery’s yard, on a bench, in the shadow of the bushes, with my notebook.

“What are you doing? What are you writing there?” the girl, who was around ten, asked me.

“I am trying to write music, but it’s not turning out well,” I said.

And then, the unexpected words from her: “Have you thanked God for this failure already?”

***

The most sensitive musical instrument is the human soul. The next is the human voice. One must purify the soul until it begins to sound.

A composer is a musical instrument, and, at the same time, a performer on that instrument. The instrument has to be in order to produce sound. One must start with that, not with the music. Through the music, the composer can check whether his instrument is tuned and to what key it is tuned.

***

God knits man in his mother’s womb, slowly and wisely. Art should be born in a similar way.

***

To be like a beggar when it comes to writing music: whatever, however, and whenever God gives.

***

We shouldn’t grieve because of writing little and poorly. But because we pray little and poorly, and lukewarmly, and live in the wrong way.

The criterion must be, everywhere and only, humility.

***

Music is my friend. Ever-understanding. Compassionate. Forgiving. It’s a comforter, the handkerchief for drying my tears of sadness, the source of my tears of joy. My liberation and flight. But also a painful thorn in my flesh, and soul. That which makes me sober, and teaches humility.

I will say a bit more. Pärt’s words spoke to me greatly, not only because his music brings me to my knees, but because my time at the monastery had a way of confronting me with many of my failures.

The failure to unclench from my preconceived ideas of productivity and simply relax into the peace and beauty around me. The failings of my body. Of the many missed opportunities for greater love, attention, and care, each small perhaps but each in the clarifying silence of the monastery grounds thrumming a resounding minor chord across my heart. The hesistance in overcoming my myriad fears, the reluctance to grow in courage, to step out of the prison of my self-obsession, whose gates, as ever, stand wide open. The struggle to open up to the love and help of others, to go beyond self-soothing isolation, the insistent need, as one of my colleagues reflected afterwards, to “attempt to do on my own what I can and should ask of others.” The ongoing struggle to give others the reciprocal gift of my vulnerability, which is the heart of community.

And all the usual tiresome faults: of half-hearted prayer, of distraction. Of failing to listen, to be patient, to gracefully accept not having the answers, to embrace Providence and trust in God, who even as I wrestled with Him was in the process of giving me things I had begged for, things that only a few months before I could not have imagined receiving, in ways I could not have imagined receiving them in “the futility of my mind.” (Ephesians 4:17)

Most importantly: the failure to give thanks for my failures. It is comforting that even the genius of Pärt needed to be reminded of this through the bluntness and innocence of a child. In my case, each of these failures was answered, often instantaneously, by an outpouring of grace, both humbling and invigorating. Grace incarnated, in the wisdom of His plan, by the Persons surrounding me, us who He created out of nothing to be workers in the vineyard together in this particular time and place: monks, priests, artists, oblates, sheep, barns, clouds, hayfields at dusk.

Pärt echoes Father Jacques Philippe, who in his book Searching for and Maintaining Peace says that, far from allowing our shortcomings to fill us with sadness and recrimination, we should celebrate them: they are the surest sign that the only source of goodness is God, whose “power is made perfect in weakness.” (2 Corinthians 12:9) Father Philippe writes: “When he cites the phrase of Saint Paul, Everything works together for the good of those who love God, Saint Augustine adds: Etiam peccata—even sins!”

One hesitates over that—and yet is it not what we profess in exulting in our “happy fault”? That God’s transfiguration of failure, the icon of His defeat of Death, is precisely the greatest arena of His power? A great paradox, a great mystery, inexhaustible.

So the point of embracing failure is not to berate ourselves, not to indulge our melancholy, nor even to punish ourselves. Increasingly I feel that it is not ever our role to punish ourselves; life does that for us, and our job is to learn to accept those penances joyfully. (Difficulty mode: impossible.) This is because self-flagellation is usually a form of inverted and narcissistic pride, of setting ourselves up as judges where we have no authority to judge. Father Philippe is very clear that this is not laxity, but humility:

“The sadness and the discouragement that we feel regarding our failures and our faults is rarely pure; they are not very often the simple pain of having offended God. They are in good part mixed with pride. We are not sad and discouraged so much because God was offended, but because the ideal image that we have of ourselves has been brutally shaken. This excessive pain is actually a sign that we have put our trust in ourselves—in our own strength and not in God.”

Failure is the doorway of trust, and thus the doorway of joy. Failure is what re-centers us, bodily, viscerally, on our total dependence on God. It brings us into communion with others, it is the stage on which Love moves from a nice-sounding abstraction to a daily reality. It beckons us to finally grow up, see the world and ourselves for what they are, and become children once again.

“Healing begins with our taking our pain out of its diabolic isolation and seeing that whatever we suffer, we suffer it in communion with all of humanity.”

—Henri Nouwen

May you bask in the cooling glow of August as the summer light dims from lemon to purple and the ceiling of the world again begins its long descent,

As ever,

J

Is this current? Re thoughts at Mount Saviour?