Thrill of Sunlight Edition

Hopper and the mysteries of Nature. Donna Tartt on art and artifice, Daniel Mitsui on traditionalism, A.E. Stallings on the unexpected word, and more.

Maybe I am not very human. What I wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house.

—Edward Hopper

But the breed of man

Has been queer from the start. It looks like a botched

Experiment, that has run wild, and ought to be

Stopped.

—Robinson Jeffers, “Orca”

O.M. believed profoundly (and in accordance with the Catholic catechism) that in Paradise Nature was perfect and did not know death. The Fall (prevarication) of Adam not only changed the situation of man, making him mortal, but also introduced death and suffering into the whole of nature. Since that moment a pained Second Nature grieves and yearns to return to its lost happiness, which can be accomplished again only through man.

—Czesław Miłosz, “Apprentice”

Friends,

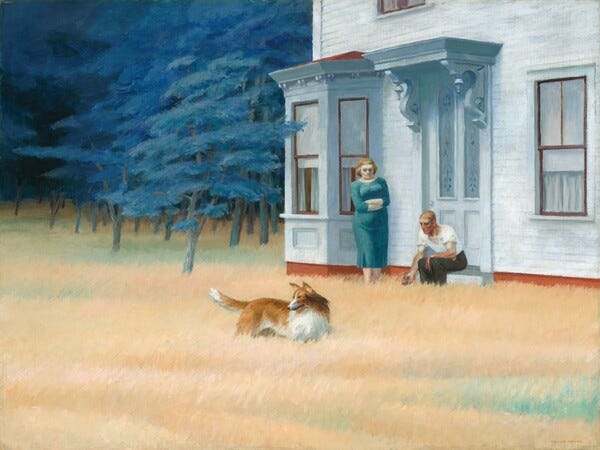

These days I’ve been looking at a lot of Hopper. (As ever.)

It’s been making me think about the relationship between interiors, cityscapes, and landscapes. That is to say, the world of humanity and its dramas vs. the world of Nature, which is all around us and which we are certainly a part of, but which we are, we intuit even if we can’t fully articulate, inescapably separate from. The human vs. the natural: the conundrum of consciousness inhering in the created world but somehow not of it, perhaps even set against it.

Yet something about this dichotomy remains unpersuasive. There’s a flaw somewhere. We may be different somehow from “the rest of nature,” but not really separate. And if we are truly different, in what sense?

Most conclude it has to do with consciousness, especially self-consciousness, but that explanation is only partial. It seems clear from the evidence of my senses that nature is conscious, too. In her individual citizens, particular animals and plants, but also, somehow, as a whole. This is not pantheism; animals are not gods and Nature is not God. It’s something stranger, God working out his plan for History through the free assent of His creation.

For neither does it seem credible that foxes or zinnias are mere automatons; they operate on instinct but they are also unmistakably Individuals. They are free and sovereign, like us, even if, unlike us, they were not subject to falling into the disordered freedom that tethers us to our own chaotic pride. Perhaps in this sense they are freer than us.

There are many explanations for the divide. I am not conversant enough with the philosophical tradition to list, much less understand them all. That humans are tool-using creatures, unlocking a feedback loop between our intelligence and our will, granting us vast powers, giving us the illusion of dominion over nature even while alienating us from it. That humans, in the image of God, are endowed with eternal souls, unlike the fallible, temporary animating spirits of our brothers. That humans mastered language, which, depending on your temperament, either revealed or invented concepts and abstractions, throwing open to us the doors of universal Forms. That humans know of time, which is to say change, which is to say death, which is to say our own mortality, knowledge which seeds us with the loneliness of longing, hope, suffering, nostalgia, and regret.

These all seem perfectly fine, though somehow incomplete.

John Berger in his deeply-felt essay “Why Look at Animals?” describes the problem yet another way, by meditating on the relationship of human and animal. The defining feature of that relationship is that we are both “like and unlike”: Like enough for recognition and communication, for companionship, for shared experiences of loyalty and love, but always interacting across an unbridgeable chasm. In meeting the eyes of an animal—in meeting, as I might take the liberty to expand the point, the eyes of Nature—we are recognized in kinship but also confirmed as separate. We see ourselves being seen by the Other, and this is how we know ourselves to be other: “Man becomes aware of himself returning the look.”

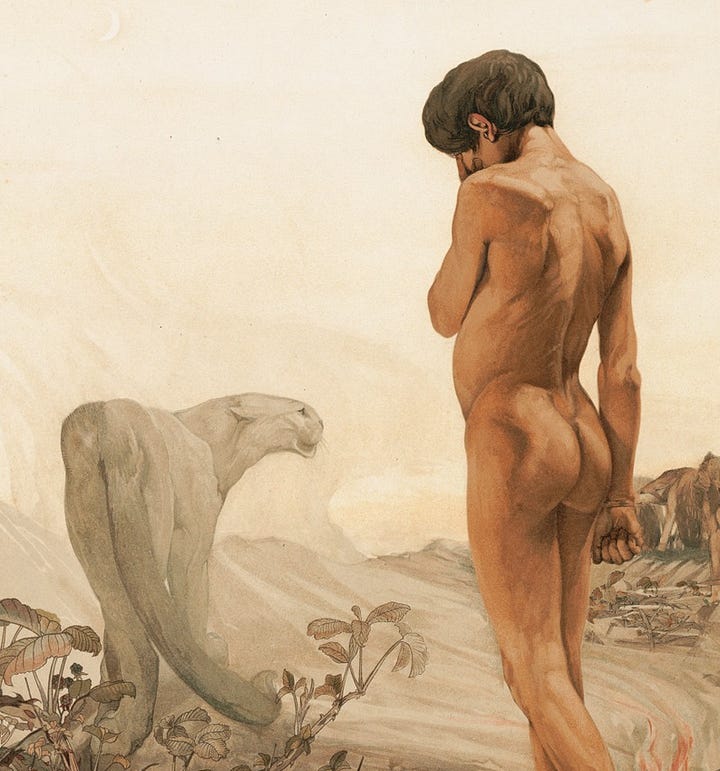

In this reading, we are not separate from Nature because of our self-consciousness, but we gain our self-consciousness precisely through our relationship with Nature, even as that relationship is self-evidently one of mutual non-comprehension and often fear. In Kipling’s Imaginarium, wild animals can love a boy as their own child, yet cannot meet his eyes for long.

Berger notes, too, that our closeness with animals bred the first use of symbolic thought: “What distinguished men from animals was born of their relationship with them.” (This is a modern literary-sociological way of restating what happens in Genesis when we are given authority to Name the animals.)

What is said about animals may also, with some modification, be said about what has come to be known as “landscape.” The packaging of scenes of ostensibly unspoiled nature has always carried an undeniable irony, that such scenes are wholly constructed, if not to say contrived, by an imposition of the human observer, for the pleasure of a human audience. Untouched nature created by us and for us.

Yet perhaps a landscape cannot return our gaze in precisely the same way as a border collie, but I nevertheless believe it does return it. It returns to us an image of ourselves as a collaborator with Nature—sometimes as a participant in it, more often as a consumer of it; sometimes as a dominator of it and other times as a worshiper of it. In all of these cases, we are both “like and unlike”—all at once in relationship with it, dependent on it, and indefinably distinct from it.

This is not to defend the fallacy of a “pure” Nature as against the corruption and absurdity of civilization, along the lines of Robinson Jeffers’ “inhumanism.” That is an ironically human romanticization.

And a complicated one. Since at least the dawn of the Industrial Age, there has been a strand in environmentalism that villainizes humanity. At its furthest extension, so beautifully expressed by Jeffers, humanity is a sort of uniquely evil and purposeless parasite, a view which has implicitly driven much of the depopulation activism of recent decades. But at the same time there is a competing strand, vaguely pagan, along the lines that humanity is not particularly special, that we are “just” animals, that we can somehow be harmlessly “reabsorbed” into the natural order.

In practical application, this doesn’t seem to work. Even in prehistory our rudimentary hunting tools helped drive the megafauna to extinction. Everywhere we walk, we are marked as different. Mowgli must leave the jungle.

So—it is impossible to divorce Nature from ourselves, since any attempt to do so simply imposes our own concepts and categories upon it; and equally impossible to fully reconcile ourselves with Nature in the aftermath of the Pandora’s box of self-consciousness, of tool-use and teamwork, of “knowledge of good and evil.”

Any honest account of the problem must be “both-and”: recognizing us, like Berger, as simultaneously “like and unlike.” We are inseparable from Nature, we are an arm of Nature, but we also have some sort of special Commission, a power and a responsibility to shape her development, which other creatures do not have, or do not have in the same way. And thus we have the power, uniquely, to fuck everything up. Again we see this found already in Genesis, and nothing in the development of industrial civilization or modern science has obviated it. To the contrary.

Burtynsky’s art, for example, is a very direct, and also very poetic, exploration of this Commission. His portraits of the awesome scope of human industrialism illustrate both the upward swing of our power, which has temporarily “lifted us” away from the previous pre-fossil fuel restraints of nature, as well as the reassertion of the undefeatable principles of decay, dismantlement, and reintegration that are in the process of bringing us “back down to earth.”

But the Earth that persists in the shadow of our industrial age will not be the same Earth of Moses and the Pharaohs, just as their Earth was not the same Earth of the Precambrian. We have not so much been “liberated” from Nature, as “pulled her onward” like draughthorses into some new equilibrium.

Which brings us back more or less to where we started. With looking at pictures of buildings and boats and factories and the infinite rooms constructed and inhabited by humans and wondering at how they can be drawn from Nature, in constant dialogue with Nature, and yet be dragging both Nature and ourselves forward into futures that neither of us could have foreseen.

Which brings us back to, contra Hopper, the very human—and yet strangely transcendant in its glowing simplicity—thrill of sunlight on the side of a house.

To Hopper’s landscapes strewn with the work of human hands, and his cityscapes that read more like landscapes, elemental and seemingly removed from communal human life and placed in some eternal register of geologic forms. To his protagonists, so revered for their enigmatic interiority, which seems to carry the same mute interiority as animals, solitary and watchful.

When Hopper depicts a looming and lonely lighthouse, or a gas station at dusk, or the interior glow of an office at night, he is participating, knowingly or not, in a long conversation on the mystery of the underlying unity and correspondence between our eternal souls and the created world. Which even under the light of Genesis, the Gospels, and Science will remain at least a partial mystery, a riddle of intense attraction, until the culmination of time.

Like the Trinity, the truth of diversity enfolded into unity, division synthesized in wholeness, is empirical, plainly apparent in the structure of reality, and yet it slips beyond our ability to fully grasp. We can only do so, tentatively, through symbols, images, colors, phrases—which both gesture toward but also participate in the mystery—having become weary, at long last, of attempting to understand it, and instead endeavor faithfully to renew, embody, and glorify it.

Links.

Donna Tartt on Art and Artifice: “Unlike artifice, art cannot be boiled down or reduced to its influences and component parts without falsifying it; its depths, which are nonlinear like dreams and unbound by time, are eerily self-renewing and inexhaustible, and they always have something new to say to us—quite often, things the artist could never have consciously intended.”

Ukraine’s short-lived Modernist golden age.

Catholic artist Daniel Mitsui on tradition and innovation: “What I would like to advise people who would consider themselves religious or artistic traditionalists to keep in mind, is that you don’t support traditional art by embracing attitudes that, if they had been held in the past, would have prevented that art from being made in the first place.”

Poet A.E. Stallings on the thrill of the unexpected word: “There are poems where you want a smooth surface, where nothing jars, but more often I like lexical texture, and I love getting in a word that doesn’t seem like it would belong.”

Philip O’Mara on visiting Marianne Moore’s apartment.

The quest to uncode Vermeer’s true colors.

Chris Arnade on the stalled American dream.

Lubec ruins offer evidence of a possible Norse settlement in Maine dating to 1000 A.D.

Sonya Mann on the pleasures of yelling into the void.

Read this conversation between Sonya and Henry Zhu on rationality and faith:

“I really like a good joke also because it’s like asking, why did you laugh at a joke? You know? And there’s a sense in which you can sort of dissect that. But really the reason is because it was funny. So it’s like the same thing with God. It’s like, why would you praise God? Okay, I can deconstruct some reasons, but the main one is because he is glorious.”

Emily Zanotti on surrogacy and Leah Libresco Sargeant on IVF.

Simon Sarris on quests, failure, and desire. “Desire is a beautiful emotion and a visceral motivator. I think you should court it with a healthy respect.”

Emma Collins on confronting the unlived life: “It’s actually good to feel the pain of what we lack and to be consumed by frustration. It is only through allowing ourselves to feel the frustration of our unlived life that we can begin to legitimately imagine satisfaction. Our culture is one of addiction, in that it too easily fills up spaces of lack with synthetic substitutes.”

Dog Fox Field revisited: “In 2022, over 13,000 people were killed by the MAiD program, making it Canada’s sixth leading cause of death.”

From my previous essay on MAiD: “The absurdity of suffering, the excruciating and seemingly pointless pain of terminal and chronic sickness, cries out not just for relief but for explanation. A narrative that places control of our suffering back into our own hands, even if those hands administer death, can appear to answer that need.”

L.M. Sacasas on embracing “sub-optimal” relationships: “A simple exhortation: we need people in our lives, not the simulation of people.”

“Learned and leisurely hospitality is the only antidote to the stance of deadly cleverness that is acquired in the professional pursuit of objectively secured knowledge. I remain certain that the quest for truth cannot thrive outside the nourishment of mutual trust flowering into a commitment to friendship.”

—Ivan Illich, The Cultivation of Conspiracy

May the flaming oranges of October light your way down the purpling boulevards and on into the antechambers of winter,

As ever,

J