Hark the Heralds Edition

David Graeber’s anarchist paleo-anthropology, Albrecht Dürer’s encounter with Aztec art, and welcome to Advent.

Happy December.

This is my semi-regular roundup of what I’m reading and working on. If you’re new, catch up on what this substack is about here. I also post occasional poetry and prose. It’s free. Subscribe here if you like.

Otherwise, welcome friend, and read on.

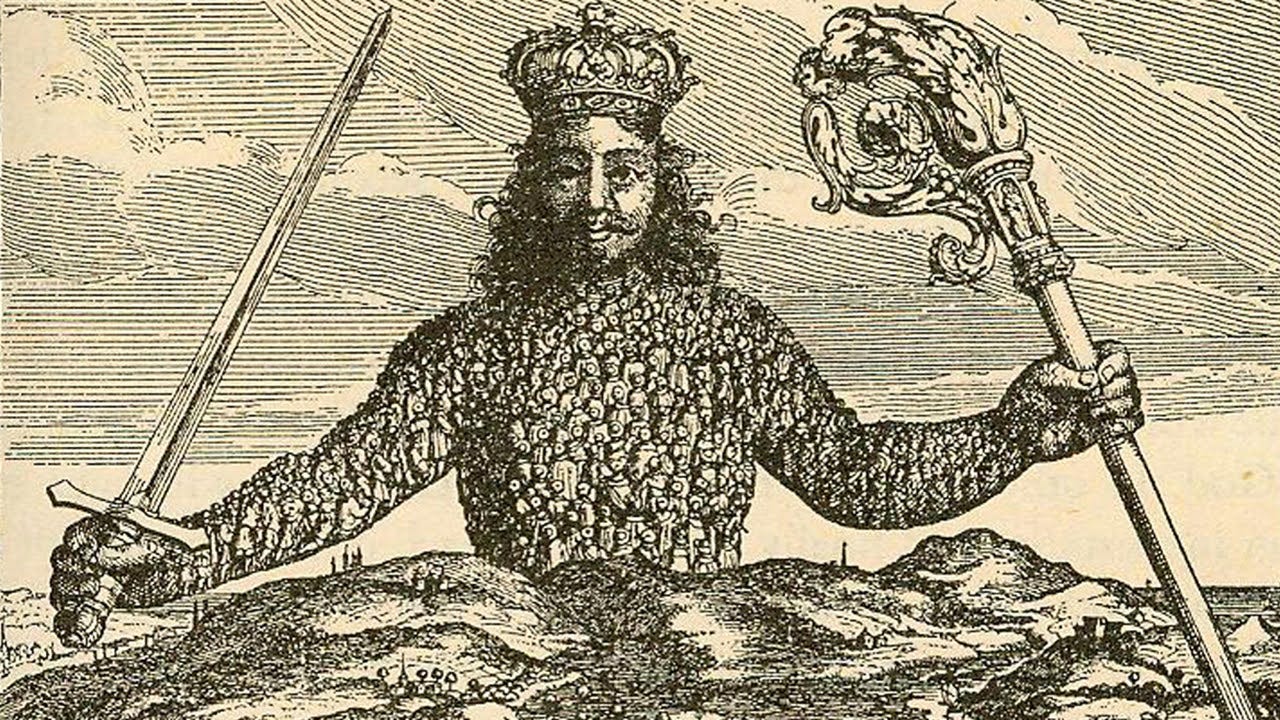

Paleo-anarchist revisionism. “The Dawn of Everything,” David Graeber’s last book, co-written with archeologist David Wengrow, seeks a total re-understanding of early human history. It hopes to upend the current potted narrative that frames history as a progressive, if not inevitable, development from hunter-gatherer (anarchical; nomadic; anti-hierarchical) to civilized (agricultural; urban; bureaucratic-centralist). Instead, they present evidence of highly complex pre-historical and pre-settlement societies that either functioned without a state or engaged with “stateness” in creative ways, such as alternating between urban agricultural life for part of the year and then disbanding into decentralization for the rest of the year.

Above all their thesis is meant, as William Deresiewicz notes in his glowing review, to challenge the fatalist notion that political history is largely the outworking of materialist forces and that humans are passive victims of technological development. Instead, we should feel empowered (as well as chastened) to accept our political and moral agency:

The overriding point is that hunter-gatherers made choices—conscious, deliberate, collective—about the ways that they wanted to organize their societies: to apportion work, dispose of wealth, distribute power. In other words, they practiced politics. Some of them experimented with agriculture and decided that it wasn’t worth the cost. Others looked at their neighbors and determined to live as differently as possible… Above all, it is a brief for possibility, which was, for Graeber, perhaps the highest value of all. The book is something of a glorious mess, full of fascinating digressions, open questions, and missing pieces. It aims to replace the dominant grand narrative of history not with another of its own devising, but with the outline of a picture, only just becoming visible, of a human past replete with political experiment and creativity.

Historian Daniel Immerwahr is more critical, calling the book “both thrilling and exasperating, showcasing the promise and the perils of the anarchist approach to history.” He takes issue with several points of fact, but more fundamentally with the authors’ failure to answer the question they set for themselves, namely: “If states aren’t inevitable, why are they everywhere?”

Justin E. H. Smith agrees with Graeber and Wengrow (and earlier work by James C. Scott) that many indigenous societies were not “pre-state” but rather “post-state”—that is, they had experienced the development of hierarchies and the domination and curtailment of freedoms that they entailed, and actively worked to set up social arrangements to limit it or prevent it from happening again. But above all he lauds their recovery of an appreciation of the subjectivity of past peoples, a recognition that they had their own complex internal experience of what it was like to be them that is just as irreducible and often bizarre as our own. The authors’ “most affecting accomplishment lies,” he writes, in “their commitment to the idea that these were real people, as weird and idiosyncratic and unfathomable by quantitative methods as you and I.”

Theology of the body. Ross Douthat’s “The Deep Places,” his latest book, departs from political analysis, covering instead his wrenching years-long battle with Lyme disease. He grapples with perennial questions such as the value of suffering and its implications for religious faith, as well as more modern concerns such as the contested nature of Lyme and the broader debate over the limits of the medical establishment. His conversation with Andrew Sullivan delves deeply into these topics. Douthat is also provocative in sketching some parallels between his own experience, the broader rise of chronic illness, and his ostensibly-unrelated thesis on our political decadence. Freddie deBoer’s review is laudatory but also skeptical of Douthat’s medical skepticism.

I also appreciated this interview, in which Douthat touches on some of the more interesting tensions in modern medicine, especially the apparent disconnect between a highly mechanistic view of the body, on the one hand, and an impulse to explain away mysterious ailments as “psychosomatic” on the other:

One of the peculiarities of this experience is that there's a sense in which official medicine on the one hand is very focused on material explanations. Any condition needs to have a material explanation. To the extent that it doesn't, it probably doesn't exist, and is psychogenic and so on. At the same time, when confronted with conditions for which there isn't an immediate material explanation, you often find that doctors are quicker than patients to retreat to the immaterial.

Anyone who has had any sort of even slightly-anomalous medical problem is familiar with this juxtaposition: that allopathic medicine is at once extremely powerful, and narrow and fragile. It is easy to reach the borders of its competence, much easier than healthy people often suppose, and precisely because its methods are so powerful, it is easy to sustain iatrogenic friendly fire. After having that experience once or five times, it’s hard for your default view not to shift at least a bit away from naive deference and closer to a hermeneutic of suspicion. But ideally, as Douthat suggests, it is probably best to eventually mature into a hermeneutic of utilitarianism: modern medicine as a tool to be applied—or not—according to an individual’s best judgment. An Illich-ian recognition that the human being always stands above the tool, and uses it, not the other way around. Whether that’s pragmatically possible under our current dispensation is another matter.

More importantly, Douthat touches on the always-pressing issue of gnosticism, the ancient heresy that, among other things, sees our material bodies only as temporary and oppressive containers for our spirits.1 Like many who struggle with prolonged physical breakdown, he takes solace in dissociating into his intellectual pursuits, finding it increasingly difficult to avoid conceptualizing the mind as the “real self” and the body as prison:

I definitely became more of a dualist in the oversimplified Cartesian sense through this experience. Because, to the extent that you're in a dark place and yet your mind still functions, and you can sort of inhabit intellectual life and debate. You really do feel the sense of your mind as something that is contained in, but somehow separate from, your body.

You have what feels like your true self in there, but in my case the body was like this cage of pain, of muscles and bones and so on in pain. As a good Catholic, rather than a Gnostic, I try to think of this in terms of the necessity of the bodily experience… And there has to be a specific good that that comes out of it. So I almost ended up with this kind of bias against strategies of prayer and meditation that are designed to separate the mind and body and soul bit by bit. I was more in a place of thinking like, okay, this is what God from his imperium is giving you. And you have to live with your body for as long as you can.

Gnosticism is a heresy because it denies the fundamental good of the created world, and thus of God, who is not only the Creator but also the ground of all Being itself. But it is a such a paragon of heresy, and why we need the Church to define it and protect us from it, precisely because it can feel so true, especially when we are in pain. Unfortunately, this is when we most need to not believe it, because its ultimate implications are life-denying and lead to escapist fantasies which leave us even more miserable. The real challenge is that it is not purely false (that would be too easy), but contains an important element of truth—that the created world is fallen and full of unnecessary suffering. As Chesterton reminded us, the danger of heresy is precisely that it is a half-truth—a seductive fragment of truth, separated out from the whole, and thus made diseased.2

Ultimately, Douthat gives a beautiful testimony of accepting his fucked-up body and God’s will, in spite of everything—something I am utterly sure in his position I would not be capable of doing:

But having the experience itself has been de-intellectualizing. You don't stand outside yourself thinking, well, am I being reasonable in desperately leaning on faith? Instead, you go to church and you get on your knees and you beg God for help. Then the rest of the time, the only answer that's forthcoming is that you’ve got to keep going and keep doing weird shit to try and get better.

“Keep doing weird shit” is, distressingly often, the only rational way forward.

RIP Sondheim. Stephen Sondheim in a 2000 interview on the fate of Broadway and popular music, his artistic process, and the pitfalls of over-seriousness: "[Young writers] are so eager to make what they write important that they start with themes instead of stories and characters."

RIP Bly. Robert Bly is best known for his role in catapulting the “mythopoetic men’s movement” to prominence with his 1990 book Iron John. He was also a bard of the endless lonesome Midwestern landscapes:

I am driving; it is dusk; Minnesota.

The stubble field catches the last growth of sun.

The soybeans are breathing on all sides.

Old men are sitting before their houses on car seats

In the small towns. I am happy,

The moon rising above the turkey sheds.

Dürer on the road. Travel journals and letters from the German Renaissance painter and printmaker Albrecht Dürer reveal his personality as an irritable, bargain-seeking tourist and canny deal-making entrepreneur. Fascinatingly, while on business in Brussels in 1520 he encounters Aztec art:

Dürer describes ‘a sun all of gold, an arm span wide, likewise an all-silver moon, also of the same size...In all the days of my life I have seen nothing that gladdened my heart so much as these things. Because I saw amongst them wonderfully artistic things, and I wondered at the subtle ingeniousness of the humans in strange lands.’ Thus, to him the ancient Mexican craftsmen were not so much devilish heathens as gifted fellow artists.

Dancer, singer, socialite, spy. St. Louis-born Josephine Baker becomes the sixth woman and first black woman to enter France’s Panthéon, the nation’s highest honor, in recognition of her service as an intelligence asset for the French Resistance. As she performed and caroused her way across the continent, she carried secret dispatches on German troop movements and other critical information. They were written with invisible ink and only capable of being revealed with lemon juice—validating all of my ten-year-old self’s knowledge of spycraft.

Music.

French-Acadian trio Vishtèn.

Cooking.

For the second Thanksgiving I made this cranberry tart, which I highly recommend even for clueless non-bakers like myself (measurements available in the video without a subscription). It is gluten free (almond flour) with a wonderful combination of nutty and sour—I might even suggest slightly reducing the sugar from this recipe.

Snow Dog.

Poetry.

We have tested and tasted too much, lover—

Through a chink too wide there comes in no wonder.

But here in this Advent-darkened room

Where the dry black bread and the sugarless tea

Of penance will charm back the luxury

Of a child’s soul, we’ll return to Doom

The knowledge we stole but could not use.

And the newness that was in every stale thing

When we looked at it as children: the spirit-shocking

Wonder in a black slanting Ulster hill

Or the prophetic astonishment in the tedious talking

Of an old fool will awake for us and bring

You and me to the yard gate to watch the whins

And the bog-holes, cart-tracks, old stables where Time

begins.

O after Christmas we’ll have no need to go searching

For the difference that sets an old phrase burning—

We’ll hear it in the whispered argument of a churning

Or in the streets where the village boys are lurching.

And we’ll hear it among simple decent men too

Who barrow dung in gardens under trees,

Wherever life pours ordinary plenty.

Won’t we be rich, my love and I, and please

God we shall not ask for reason’s payment,

The why of heart-breaking strangeness in dreeping

hedges

Nor analyze God’s breath in common statement.

We have thrown into the dust-bin the clay-minted

wages

Of pleasure, knowledge, and the conscious hour—

And Christ comes with a January flower.

—Patrick Kavanagh, “Advent”

What I’ve been working on.

Charcoal portrait of a woman, 11x14in.

Watercolor of pomegranate and onion.

I also cleaned my studio.

The liturgical life.

Last Sunday marked the beginning of Advent, which is also the beginning of the liturgical year. Happy new year! Advent continues for four weeks until December 25th, the feast of Christ’s birth.3

A season of preparation, Advent commemorates in a particular way the entire epoch of history before the Incarnation—defined by conflict, covenant, betrayal of covenant, slavery, plague, wandering in the desert, prophecy, and expectant waiting for the Messiah. In these weeks we read the Old Testament prophecies alongside the New Testament accounts of St. John the Baptist, the Forerunner.

This preparation is joyful, since we know the end of the story, but also penitential, since we must put ourselves in good order for the arrival of the King. Advent has long been known as the “little Lent,” (the Irishman Kavanagh’s “dry black bread and the sugarless tea of penance”) though Western fasting disciplines have now been almost totally abrogated. Dark purple vestments are used, and the traditional liturgies veiled images and limited music, as during Lent. It is a hopeful season, yes, but also, as I once heard a good priest explain, one of at least a little taste of fear and confusion—a taste of the bitterness of living in a world without Christ. A desert world, in which the earthly reign of power, domination, and suffering stretches to a seemingly endless horizon, in which hope is felt less as gleeful anticipation than as desperate thirst, in which no one is quite sure if the Baptist’s “voice of one crying out in the wilderness” is that of a prophet or a madman.

It’s notable that, despite the modern hyperfocus on Christmas, it was a late addition to the Church calendar, with celebrations only becoming widespread in the 4th century. Even then, different localities used different dates, it was not elevated to a universal feast until centuries later, and the term “Christmas” was a 12th Century Old English neologism.

Indeed, in a sign of the Nativity feast’s innovative nature, the great Eastern saint, John Chrysostom, had to explain it to his congregation in a sermon from 386 A.D., which we can now profit from:

A feast is approaching which is the most solemn and awe-inspiring of all feasts. If one were to call it the metropolis of all feasts, one wouldn’t be wrong. What is it? The birth of Christ according to the flesh. In this feast the Epiphany, holy Pascha, the Ascension and Pentecost have their beginning and their purpose. For if Christ hadn’t been born according to the flesh, he wouldn’t have been baptized, which is Epiphany. He wouldn’t have been crucified, which is Pascha. He wouldn’t have sent the Spirit, which is Pentecost. So from this event, as from some spring, different rivers flow—these feasts of ours are born.

May whatever feasts you call your own this December, whether the sprawling metropolis or solitary village kind, be full of joy, conviviality, and peace, as well as eggnog, booze, roast goose, etc, and all other good things.

As ever,

J

I’m a poor philosopher but to the best of my understanding the Christian view affirms along with Aristotle that while soul and body are distinct, they are also a unity and not truly separable: “The soul is the form of the body.” We are as much our bodies as our souls, and it is crucial to affirm that Jesus was bodily resurrected, scars and all, because this is the same manner that our bodies, along with all of creation, will be physically restored in eternity.

“Every heresy is a truth taught out of proportion.” G.K. Chesterton, 1909.

Referring to the West, since I am Latin Rite; Eastern rite churches are on a divergent calendar and celebrate Christmas in January. Their liturgical year is also structured differently.

Will definitely be adding "The Deep Places" and "The Dawn of Everything" to my to-read list. Thanks for the reviews!